(The following is an excerpt from a story featured in Weird NJ issue #9.)

AFTER BEING TRIED, CONVICTED AND EXECUTED for the triple murder of one of Morristown's most respected families, the story of Antoine Le Blanc should have been over. But his public hanging on the town green was really just the beginning of a tale so gruesome that Morristonians still recoil at its telling more than one hundred and sixty years after the incident. For it is said, that the remains of Antoine Le Blanc may rest in pieces, to this day, amongst the treasured family heirlooms in some of the finest homes of New Jersey.

Le Blanc, a French immigrant by way of Germany, arrived in New York in April of 1833. After three days in the new world, he was hired as a hand to work the family farm of Samuel Sayre of Morristown, N.J. In exchange for his hog slopping and wood chopping labors, Le Blanc was afforded a small room in the dank basement of the Sayre house -- but no wages. He took his work orders from Mr. Sayre, his wife Sarah, and even the Sayre's household servant Phoebe, who is believed to have been a slave. Being the privileged son of a well-to-do European family, this arrangement probably did not sit too well with the thirty-one year old Le Blanc.

It was about two weeks after he first started his menial chores on the Sayre farm that Le Blanc decided that he could suffer the indignity no longer. He began to plan his revenge. On the night of May 11, Le Blanc returned to the Sayre house at about 10:30 pm, after drinking at a local tavern. Faking distress, he summoned Samuel Sayre out to the stable, where he said that there was a problem with the horses. Carrying a candle, Mr. Sayre made his way out to the barn, where Le Blanc proceeded to smash in his employer's face with a shovel, splattering pieces of Sayre's brain all over his coat. The killer then repeated his ploy on Mrs. Sayre, finishing her off with a kick to the head from one of his heavy boots. After hiding the two bodies beneath the nearby pile of manure, Le Blanc made his way back to the main house, where he found Phoebe asleep in her bedroom on the second floor. Le Blanc then caved in the unsuspecting girl's skull with a single blow from a club.

After his murderous spree Le Blanc frantically stuffed whatever household valuables he could into pillowcases and set off down the road atop one of the Sayre's horses. In his haste to escape the scene of the crime, he unknowingly left a trail of stolen booty in the roadway which would later mark his route. On the morning that followed, Lewis Halsey, a Sayre family friend, discovered some personal effects in the road which bore the monogram of Samuel Sayre. Fearing a robbery had taken place, a group of townsfolk decided to search the Sayre property. After the grisly discovery of the three murdered victims, Sheriff George Ludlow set off in pursuit of the killer. When he caught up with him, Le Blanc was sipping cider in the Mosquito Tavern in the Hackensack Meadows, a pouch of Sayre's possessions by his side. According to his subsequent jail cell confession, Le Blanc had stopped to rest en route to New York, where he planned to board a ship bound for Germany. Upon spotting Sheriff Ludlow, Le Blanc bolted for the back door of the tavern, but was easily apprehended and transported back to Morristown for prosecution.

The trial of Antoine Le Blanc, for the murders of the Sayre Family, began in courtroom number one of the Morris County Courthouse on August 13, 1833. After being afforded all of the formalities of a fair hearing, a jury took twenty minutes to find the defendant guilty. The next day, Judge Gabriel Ford handed down the sentence. Le Blanc was to "be hanged by the neck until dead," and then "be delivered to Dr. Isaac Canfield, a surgeon, for dissection."

On the afternoon of September 6th, Le Blanc stood atop the "modern" gallows erected on the village green for the occasion. This new device was designed to jerk the condemned man upward, rather than dropping the floor out from beneath him. A crowd, estimated at between ten and twelve thousand, had descended upon Morristown, greatly outnumbering the local population which was about 2,500 at the time. The jeering mob, many of whom carried bag lunches, made their way into tall trees and onto nearby rooftops to get a better view of the execution.

When the counterweight dropped, Le Blanc shot up in the air about eight feet. His body twitched for about two minutes at the end of the rope, and then was still. Just over four months after first setting foot on American soil, Antoine Le Blanc's life was ended. But the truly barbaric story that still haunts Morristown to this day was just about to begin.

It seems the good, god-fearing Presbyterian townsfolk were not content to let this murderous scoundrel get off with just a mere hanging. they had some other, more creative ideas of what to do with this monster.

First, Le Blanc's lifeless body was cut down from he gallows and whisked across the street to Dr. Canfield's office. Then, the good doctors Canfield and Joseph Henry conducted some rather unorthodox medical experiments, using Le Blanc as their unwitting lab rat. Hooking the corpse up to a primitive battery, the doctors endeavored to prove a prevailing theory of the time which linked electrical current and muscular motor impulses. Although unable to resurrect the dead man, the scientists reportedly got Le Blanc's eyes to roll around in his head, caused his limbs to tense somewhat, and even elicit a slight grin from his dead lips. Frankenstein's monster though, he was not.

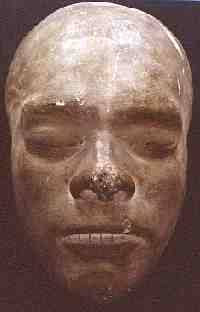

After the good doctors had completed their efforts to advance medical science, a death mask likeness of Le Blanc's face was cast in plaster. Then it was time to carve him up. Le Blanc's skin was peeled off and dispatched to the Atno Tannery on Washington Street to be fashioned into a variety of "charming little keepsakes." A large number of wallets, purses, lampshades and book jackets were produced from the hair follicle studded hide. Strips of skin were sold on the streets, each one personally signed by the honorable Sheriff Ludlow to verify its authenticity. These grisly little souvenirs reportedly found their way into many a respectable Morristown home, where, it is said, many still remain to this day.

The wallet made from Le Blanc's skin

As the years passed most of the residents of Morristown seemed content to let this dark episode of local justice slip quietly between the pages of the town's history. the story of Antoine Le Blanc, however, proved to be harder to kill than the man himself. Rumors concerning the whereabouts of Le Blanc's remains continued to circulate around the area long after the 1833 dissection. One such local legend was that Dr. Canfield had reassembled the executed man's skeleton to hang in his office. This myth was disproven, however, in 1893, when workers building an addition to the county clerk's office found Le Blanc's missing bones in a small wooden box in the bowels of the old building.

Then, on Halloween night 1995, a startling discovery was made which confirmed many of the long standing rumors concerning the survival of Antoine Le Blanc's epidermal memorabilia in Morristown. While liquidating the estate of the late Carl Scherzer, workers from Dawson's Auctioneers and Appraisers of Morris Plains uncovered the glazed plaster death mask of Antoine Le Blanc stashed away in a box in Scherzer's basement. Soon after this grim discovery, a shriveled change purse made from what appeared to be human skin was found tucked away in an upstairs library of the same house. Scherzer, a retired surveyor, had evidently amassed quite a collection of nineteenth century artifacts during his lifetime. After his death in 1979, the chore of sorting through his museum-like house fell upon the shoulders of his son Douglas, who in-turn called Dawson's.

The death mask of Antoine Le Blanc, along with the skin accessories, were put on display in a glass case at Dawson's, but were not offered for bidding to the packed house at the November 18th auction. After the display was dismantled, the Le Blanc trinkets were presumably returned to the custody of the surviving Scherzer -- or were they? When Weird N.J. phoned a representative of Dawson's, they were not very forthcoming about the Wallet man's whereabouts. They suggested we try asking around at the Morristown room of the local library. We did, but found only non-skin book jackets on their shelves. We decided to return to the scene of the crime.

Over the years the Sayre house, at 217 South Street, has been home to a number of taverns and eateries, including the Turnpike Inn, Society Hill, and Argyles. Today, it is Phoebe's Restaurant, named for the servant-girl who was brutally slain there, and whose spirit, it is said, still haunts the building. Stories of doors opening and closing by themselves, and chilly breezes blowing up the stairway to Phoebe's room have long been part of the house's legend. As we bellied up to the bar, current employees told us of lights going on in the middle of the night, that nobody could even locate the switches for. Somebody had once even felt a cold hand on their shoulder while completely alone upstairs. The bar staff told us that nobody there wants to go down to the basement after closing time, and one time somebody witnessed a lighted candle moving through the rooms of the house with no one carrying it.

We asked the manager on duty if he was familiar with the Antoine Le Blanc saga. "Yes," he said, he did remember reading something about it. "Where might we find the skin?" we inquired. "I think they've got all of that stuff over at the Morris County Museum now," he replied. We gulped the remainder of our beer and set off down the road again with just fifteen minutes left before the museum closed for the day.

"No," said the curator of the Morris Museum, when we asked to see the wallets, "That's awful! We don't have anything like that here." Then she added "Try MacCulloch Hall." We called MacCulloch Hall Historical Museum the next day and spoke with the director.

"Yes," he said, "we know the Scherzer collection quite well, but we don't have any of those Antoine Le Blanc relics. I think I do remember somebody at Acorn Hall mentioning that they had them over there." It was starting to look as though this Le Blanc got around town more than that stiff in "Weekend at Bernie's". We began to wonder if we were involved in some kind of historical shell game.

Acorn Hall, headquarters for the Morris County Historical Society, proved to be as skinless and boneless as a Purdue chicken breast. "Try historic Speedwell," was the only advice they'd offer us.

At Historic Speedwell in Morristown is the house where Alfred Vail and Samuel Morse first demonstrated electro-magnetic telegraphy, the forerunner to modern instantaneous communication. So what could they communicate to Weird N.J. concerning the hide and seek game of Le Blanc paraphernalia? "Try Dawson's Auction House," they told us.

And so it was that our quest for the wallet man came full circle, and we found ourselves on the doorstep of Dawson's in Morris Plains. After being buzzed into the gallery of tagged antiques and high priced bric-a-brac we approached the owner of the establishment. "Bring us the head of Antoine Le Blanc!" we demanded. But unfortunately, he could not. It seems that after a year and a half of collecting dust in one of the auctioneers offices, the death mask and skin items had been returned to Douglas Scherzer, just days before our visit to Dawson's.

"You could try asking Mr. Scherzer to see them," we were told. "He's easy enough to find, he's the chief of police."

Somewhat dizzy from the run-around we had been getting, I must admit that I was a little surprised by Chief Scherzer's response when I phoned him and requested to photograph the Le Blanc death mask.

"Sure," he said, " I don't see why not. I'll bring it into the station house with me. If you want to, you can come here." We set a date to get together, and then I asked him if he might have any other Le Blanc paraphernalia in his possession that could be of interest to us.

"Yes," he replied softly, after a tentative pause, "I have some other things."

"Could you bring in these other things for us to see too?" I asked, being careful not to tip my hand. "Okay," he said.

Two weeks after my phone conversation with Mr. Scherzer, Mark Sceurman and I strolled into the Morris Plains Police Station and asked the officer behind the bullet-proof window to let the chief know we had arrived. We were told to have a seat and that he would be with us shortly. I sat down and watched Mark as he paced back and forth across the waiting room floor, clipboard in hand. The minutes ticked by. After our long journey to find these all but forgotten historical artifacts, here we were, under the same roof as the objects of our quest. Seven, eight, nine, minutes elapsed. I was nervous, and I could tell Mark was also. How do you ask a complete stranger if you can see his souvenirs of human skin? What is the proper etiquette in such a situation as this? These are the questions that I think both Mark and I were asking ourselves, when all of a sudden a door swung open before us.

"Mark, hello. Hello Mark." There in the doorway stood Chief Scherzer, smiling and addressing each of us with one hand holding back the heavy door to invite us in. Balanced on his other hand was a brown cardboard box with "HEAD" scrawled across it in black magic marker.

Douglas Scherzer turned out to be a younger man than I had anticipated -- maybe forty. He was friendly, joking as he lead us to a small, bright room in the back of the station house. Once there he set the tattered parcel down on a formica table and talked openly about what he know of the Le Blanc matter, and of his own father's collection of historic momentos.

"They didn't just cast his head you know," he told us. "They also skinned him and made wallets from his hide."

"Do you have any of those wallets?" I asked sheepishly. He motioned toward the box, which lay still closed at my elbow. I felt like a kid beneath the tree on Christmas morning waiting for his parents' permission to begin unwrapping.

"Let's see what's in the box," I said finally, unable to contain my curiosity any longer. Chief Scherzer folded back the corrugated top flaps of the package, and removed some crumpled up newspaper. He then reached inside and unraveled a white towel to reveal the peaceful face of Antoine Le Blanc. As if merely sleeping, the delicate plaster eyelids closed gently over gracefully intertwining lashes. The pronounced cheek bones sloped down to the broad, smooth lips, which betrayed no expression one way or another. The hollow plaster head seemed to be an almost perfect portrait of the dead man, until you notice that both ears had been hacked off before the cast was made. Perhaps this was merely a way to ensure the easy removal of the mold from the corpse's head, or maybe the ears were just two more trinkets to be sold on the open market. Affixed to the shaved crown of the eggshell white cranium was a small paper tag which stated in 19th century script, "Antoine Le Blanc a Frenchman - murdered Judge Sayre and family - hanged in Morristown, N.J. 1833."

I picked up the fragile sculpture and began to turn it over and over in my hands, inspecting every wrinkle on the dead man's face. Like Hamlet pondering the skull of poor Yoric, I gazed into the closed eyes of Antoine Le Blanc, and at long last, felt that I knew him well.

I set the head down on the table and stepped aside to allow Chief Scherzer to remove the remaining contents of the box. He pulled out a dusty old eight by ten picture frame and handed it to me. Behind the glass was a yellowed newspaper article concerning the Le Blanc case, stuck to a piece of white matte board. Below that, fallen away from the spot where it had originally been mounted, was a small rectangular wallet. It was about four and a half inches long, and a sickly greenish-brown in color. It folded over, and a tongue flap fit neatly into a slot on top to close it. I had never seen anything like it before. This was not the tough, yet supple hide of a cow or pig, which we are all familiar with. Nor was it the shiny, rough and scaly skin of a reptile. This was a thin and frail skin which should never have been tooled in such a manner. This skin was cracked and withered. This was the decaying flesh of a human being. Beneath the dislodged billfold there was an inscription typed on a strip of paper which was also peeling away from the backing board. It read, "A wallet made of human skin allegedly that of Antoine Le Blanc." We took some photographs and then thanked our host for his time.

And so, it would seem, that reminders of this macabre episode in New Jersey history will keep finding their way into the collective consciousness of Morristown. But what has become of the dozens of remaining souvenirs which were culled from the tanned hide of Antoine Le Blanc? We don't know. But with the autumn garage sale season once again upon us, don't be surprised if you bump elbows with a Weird N.J. reporter while canvassing those roadside folding tables. For Antoine Le Blanc will undoubtedly rest in pieces, scattered throughout Morristown, for some time to come, and an old wallet, once a genuine hide, could turn out to be a real find.

Below is another example of Historical human skin

THE RED BARN MURDER

The Red Barn Murder was a notorious murder committed in Polstead, Suffolk, England, in 1827. A young woman, Maria Marten, was shot dead by her lover, William Corder, the son of the local squire. The two had arranged to meet at the Red Barn, a local landmark, before eloping to Ipswich. Maria was never heard from again. Corder fled the scene and although he sent Marten's family letters claiming she was in good health, her body was later discovered buried in the barn after her stepmother claimed she had dreamt about the murder.

Corder was tracked down in London, where he had married and started a new life. He was brought back to Suffolk, and, after a well-publicised trial, found guilty of murder. He was hanged in Bury St. Edmunds in 1828; a huge crowd witnessed Corder's execution. The story provoked numerous articles in the newspapers, and songs and plays. The village where the crime had taken place became a tourist attraction and the barn was stripped by souvenir hunters. The plays and ballads remained popular throughout the next century and continue to be performed today

William Corder's skin

Corder was hanged before an audience of thousands shortly after noon on August 11 1828, just three days after the trial ended. People had travelled from miles around, even from London, to witness the event. Some had arrived as early as five in the morning to get a good view. There were many women in the crowd, some dressed in the most fashionable clothes. On the scaffold, Corder again confessed his guilt. Writer Curtis, who witness the event, described the hanging:

"Everything being completely adjusted, the executioner descended from the scaffold, and just before the Reverend Chaplain (Reverend Mr Stocking) had commenced his last prayer, he severed, with a knife, the rope which supported the platform, and Corder was cut off from the land of the living. Immediately he was suspended Ketch grasped the culprit around the waist, in order finish his earthly sufferings, which were at an end in a very few minutes. In his last agonies, the prisoner raised his hands several times; but the muscles soon relaxed, and they sank as low as the bandage around his arm would permit."

Corder's Bust at Moyse's Hall Museum

Corder's Death Mask

Corder's preserved scalp

The body was taken down after and hour and removed to the Shire Hall where it was cut open from throat to abdomen to expose the muscles. The public were then allowed to file past to view it "divested of all its clothing, excepting the trowsers and stockings." The doors closed at 6pm and the body was prepared for the casts to be made. Both head and face were shaved. Curtis remarks "The countenance did not appear much changed, except that the under lip was drawn down so as to expose the teeth in the upper jaw: this had the effect, in a great degree, of obliterating the indentation which in life was very observable on the top of the chin. There appeared to be a considerable effusion of blood about the neck and throat, occasioned by the pressure of the rope in the moment of strangulation." The body was afterwards taken down for dissection to the County Hospital "in a state of nudity" the hangman having claimed the trousers and stockings as a "matter of right". The dissection began the next day. Parts of the body were preserved. The scalp with one ear attached, along with other relics of the murder, can still be seen at Moyse's Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds.

No comments:

Post a Comment